The future of human-computer interaction in the era of AI

Wednesday, February 21, 2024

This week, researchers and practitioners will gather at MBZUAI for the third AI Quorum of the academic year, which will focus on the future of human-computer interaction in the age of ubiquitous AI.

The gathering is set up to be a fascinating confluence of ideas from several different disciplines, including learning technologies, accessibility and health, and human-robot interaction. Participants include experts from institutions such as University College London, University of Chicago, University of Texas at Austin, University of Glasgow, Monash University, Apple, Google and Microsoft.

“The people invited to the AI Quorum know how to think deeply about grand societal challenges that human-computer interaction should play a role in resolving in this era of ubiquitous AI,” said Justine Cassell, one of the chairs of the gathering. Cassell is dean’s professor in the School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University, senior researcher at Inria Paris and founding international chair at the PRAIRIE Paris Institute on Interdisciplinary Research in AI.

The workshop is part of the AI Quorum, a series of winter gatherings at MBZUAI aimed at spurring groundbreaking AI research and promoting a broader understanding of AI’s potential as a force for social good. These meetings bring together a group of the world’s brightest minds to forge a research agenda that not only envisions AI’s potential but also charts a course towards realizing it. The previous AI Quorums focused on federated and collaborative learning and statistics in future of AI.

How people and computers function

As its name suggests, human-computer interaction (HCI) is a broad, interdisciplinary field that focuses on the ways and contexts in which people interact with and use computers. It draws on insights from computer science, design, linguistics, psychology and other disciplines. One of the core goals of HCI is to improve the interactions that people have with computers by making machines that are more receptive to the varied needs and preferences of people. It’s concerned not only with making better interfaces that improve efficiency and user experience, but also the psychological, social and cultural aspects that are associated with the use of computers.

HCI has been around for decades, and during that time, the ways in which people interact with computers have changed dramatically. Computers have become smaller, more powerful and more prevalent. Tasks that once required specialized knowledge of computer languages can now be accomplished with little expertise. Instead of coding, we can simply speak.

In some cases, at least.

[wps_image-left image=”https://staticcdn.mbzuai.ac.ae/mbzuaiwpprd01/2024/02/Justine-Cassell.jpg” caption=”Professor Justine Cassell” first-paragraph=”And yet, as humanity’s interaction with computers increases and they become more ubiquitous, it’s essential for researchers and practitioners to consider how the machines of today and those of tomorrow can be designed to serve the diverse needs of people, Cassell said. ” second-paragraph=”“A lot of people think there is no longer a need for HCI. They think that we can just give the system a billion documents, and they will know how to have a conversation with people. Or we just build self-driving cars, and they will know how to drive,” she noted. “But we know in both those cases that it’s wrong.””]

“We need to know how people function, in order to build computers that function.”

Breadth and depth

Cassell’s background spans psychology, linguistics and literature, which she admits is unusual training for someone who works in the field of computer science. And yet, “I use each of those disciplines every day and they are essential to what I do,” she said. She’s interested in the way people talk with each other, the conversations that they have and the ways communication can build connections with others and bring meaning to peoples’ lives.

Computers, of course, aren’t a requirement for people to build connections between each other, but in our contemporary lives, many people can benefit from interacting with machines, even in ways that were traditionally the domain of other people.

“In a perfect world, there would be a human available for us to talk to at any moment, but that’s not the case,” Cassell said. “One of our most important needs in life is to be listened to and it greatly influences our health. Yet we tend to not want to wake our partners in the middle of the night to have a conversation about something that worries us. And many people don’t have a spouse or a partner in the first place.”

And while some are looking to bend another’s ear, there are those for whom talking isn’t easy, Cassell said. People with conditions such as autism spectrum condition, for example, can have difficulty interacting and communicating with others and thus struggle to build the bonds that are so important for health and development. “Virtual peers can be used to practice social bonding and the kinds of conversations that can help people build these important connections,” Cassell said.

HCI-informed AI applications also have the potential to be applied to help tutor students. But to be effective in improving academic outcomes, an AI-driven tutor can’t simply reply to any question it receives or spit out technical knowledge. There is a great deal of specialized expertise, nuance and technique that is required to be an effective tutor. “We know that with real kids in a peer tutoring environment, if there is a rapport bond between the kids, they will learn more,” she said. “We are now looking at how these kinds of insights can be applied to virtual peer tutors.”

HCI can also be used to improve the functionality of chatbots by drawing on insights from disciplines such as psychology and linguistics, Cassell explained. “When people have conversations, they are always trying to figure out if they are speaking in a way that is understandable and they adjust what and how they are speaking so that it can be useful. This is called conversational grounding in linguistics and chatbots have trouble assessing the knowledge state of the interlocutor.”

In sort, the Quorum is designed to provoke thought on the foundational purpose of building technology that truly enhances human life, steering away from the creation of gadgets for their own sake.

“We’ve organized this in an edgy way,” Cassell said. “During the first day of the event, people will share provocations about grand societal challenges in how to build computers that make people’s lives better. Forget the widgets and gadgets. Forget building things because we can.”

“What does it mean to build things because we must?”

Related

Intelligent, sovereign, explainable energy decisions: powered by open-source AI reasoning

As energy pressures mount, MBZUAI’s K2 Think platform offers a potential breakthrough in decision-making clarity.

- case study ,

- ADIPEC ,

- K2 Think ,

- IFM ,

- reasoning ,

- llm ,

- energy ,

- innovation ,

- research ,

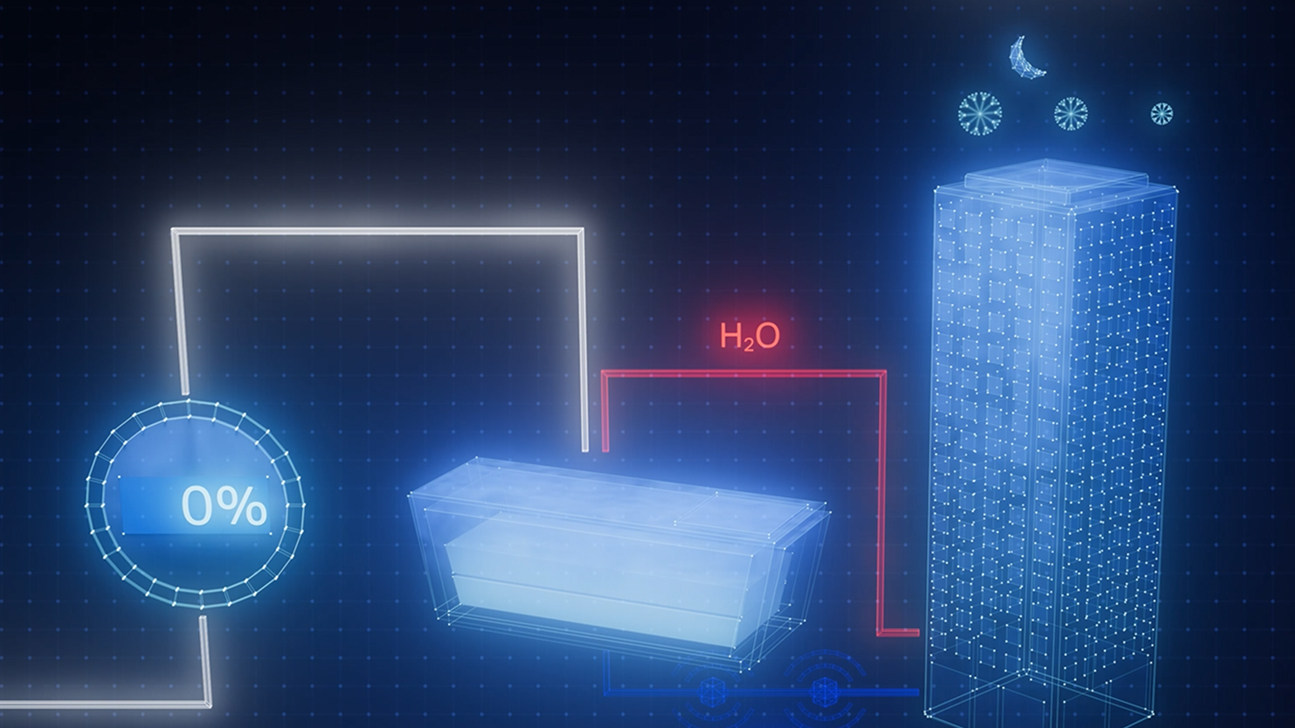

Cooling more people with fewer emissions: intelligent, efficient cooling with AI and ice batteries

MBZUAI's Martin Takáč is leading research to develop an AI-driven energy management system that optimizes the use.....

- energy ,

- cooling ,

- solar ,

- ADIPEC ,

- sustainability ,

- innovation ,

- research ,

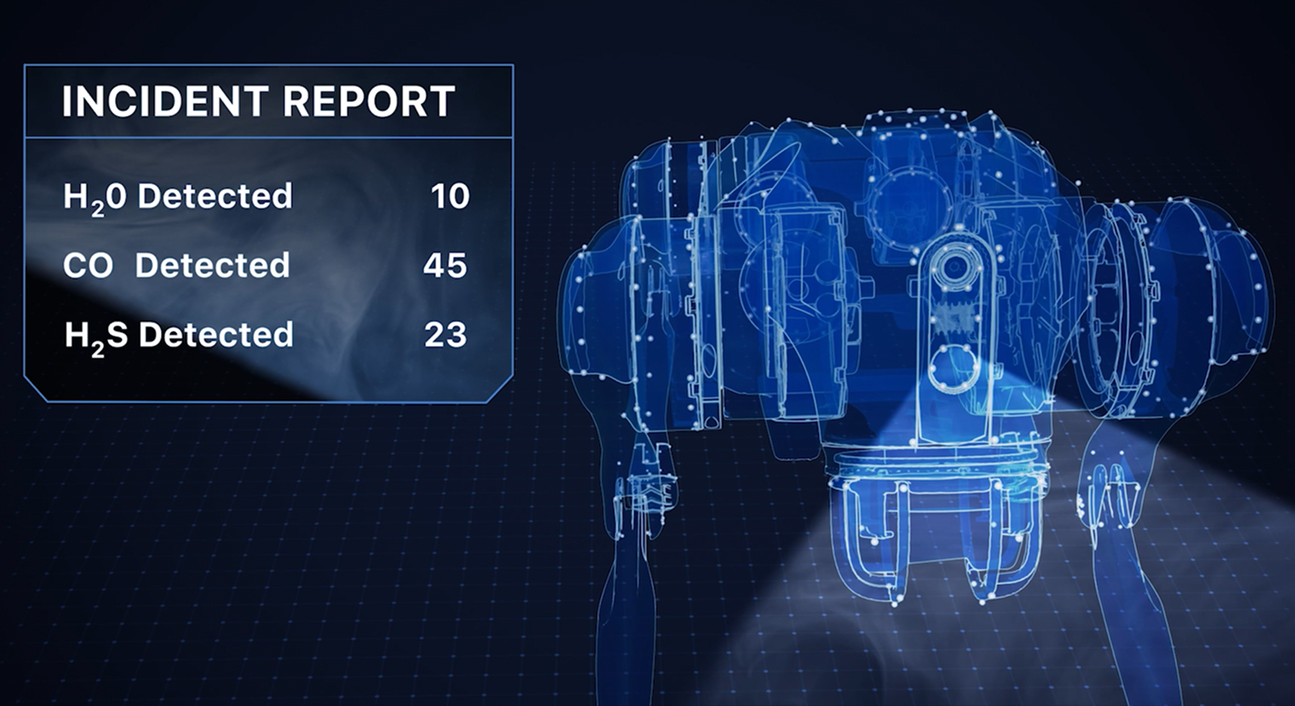

Faster, safer and smarter inspection: AI-powered robotics for industrial safety

MBZUAI's autonomous robotic system, LAIKA, is designed to enter and analyze complex industrial environments – reducing the.....

- research ,

- autonomous ,

- case study ,

- innovation ,

- infrastructure ,

- energy ,

- industry ,

- robotics ,