Nobel Laureate Michael Spence on how AI is redefining the global economy

Monday, October 06, 2025

Image: Niccolò Caranti, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Renowned Nobel Prize-winning economist, Michael Spence, gave a recent virtual guest lecture at MBZUAI based on macro AI productivity – exploring how artificial intelligence is poised to reshape productivity and growth across global economies.

Professor Spence won the John Bates Clark Medal in 1981 and shared the 2001 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with George Akerlof and Joseph Stiglitz for their pioneering work on information asymmetry and market signaling – a cornerstone of contract theory.

As one of the world’s most influential economic thinkers, he has shaped debates on growth, global economy, and information-rich technologies, holding senior posts at leading universities around the world and contributing to international institutions and policy forums.

Currently the William R. Berkley Professor of Economics and Business at NYU Stern, and Dean Emeritus of Stanford Graduate School of Business, Professor Spence spoke with us to discuss the broader implications of AI for economics, and the future of global digital policy.

You won the Nobel Prize for showing how markets work when one side knows more than the other. Do you see similar ‘information gaps’ playing out with AI today?

There are certainly informational gaps and asymmetries in the AI world, especially around LLMs. For example, without some kind of declaration, it is hard to know if something written is the product of a person or an AI. LLMs make it easier to fool people because it eliminates the kinds of mistakes that people in fraud make – such as mistakes with language.

That said, the internet – epecially now, powered by AI – is closing informational gaps by lowering the time, cost, and difficulty of acquiring knowledge and expertise. This effect – the lowering of certain key elements of scarcity in the economy – can have profound effects in the longer run.

Market signaling was central to your Nobel work – do you think companies and governments will need new kinds of ‘signals’ to build trust in AI systems?

They will, in various ways. They will look for signals that cannot be easily imitated to communicate trustworthiness. One example is giving people reliable ways to check on the veracity of what they are reading or being told. They will also need regulation that works because it increases the cost of delivering misleading information. We already have this kind of thing: an example would be financial disclosure laws and regulations.

Contract theory is about designing incentives when people don’t share the same information. What kinds of incentives or contracts might be needed to guide safe AI development?

This is an area that deserves further thought. Contracts in a world of imperfect information are structured in such a way that the contractees make choices that, in effect, reveal the private information that they possess. Right now, AI systems are being used to screen applicants for jobs. There is a real risk for both bias, and also missing ‘outliers’ – that is, people that the AI screens out that a more personal process might not. We need to be concerned about the quality as well as the cost of screening.

What do you see as the most interesting aspects of today’s economic landscape – especially since the AI boom.

There are two aspects that stand out for me. One is the rapidly evolving AI landscape and its potential impact on all economies, both positive and negative, in terms of productivity, growth, inclusiveness, inequality, and access to basic services.

The other is the transformation of the postwar architecture of the global economy into something different and as yet not fully determined. That said, it will be more complex, less integrated, and it will have a much larger set of influences guided by national and economic security considerations.

Basically, the postwar architecture was driven by efficiency and comparative advantage considerations, with relatively little sense of the risks associated with specialization. The emerging new architecture is much more focused on risks, and resilience with respect to them. The trade-offs between efficiency and security are being assessed in a very different way now.

What lessons can history teach us about how quickly AI’s productivity gains might show up in the global economy?

History is fairly clear on this. Major technological developments start to have effects fairly quickly but in isolated sectors and companies. The big effects, however, take many years to play out. In part, this is because people and organizations take time to change their behavior – to learn new things, to experiment, and so on. It is also, in part, that a major scientific or technological development leads to follow-on innovations. These then get looked at and eventually adopted.

There is clear evidence that the diffusion process with respect to innovation is not necessarily rapid – that it can be affected by policy, and that it varies considerably across sectors.

AI is a general-purpose technology, which means it has applications across the entire economy. Its largest impacts won’t, however, be seen until the diffusion process extends to all sectors, all sizes, and all types of enterprises.

Do you think AI-driven productivity growth will be concentrated in advanced economies, or can it also transform opportunities in emerging markets?

No. It may come a little faster in advanced economies relative to some emerging economies, but there is a variation. I wouldn’t be surprised to see AI adoption and impact to be faster in China than in many advanced economies.

There is no reason I know of to expect AI impacts to be confined to developed economies or to be larger in developed economies. All this refers to adoption and use of AI.

The development of new AI is different, because it requires scale, a high concentration of talent, and a considerable amount of costly computing infrastructure. I expect the major developments in this area to be concentrated, though the rapid growth of open-source AI development is significant and coulde expand the development footprint.

But to summarize, for the next decade or more, the development is likely to be more concentrated nationally than the adoption and use.

What policies or frameworks are needed to make sure the benefits of AI don’t simply widen global inequality?

This is an important question, with lots of diverse views. It has many dimensions, and diffusion is part of the answer. That means capacity and access across a wide range of countries.

Within national economies, it is crucial to achieve a reasonable balance between automation and augmentation. That is, replacing people in certain jobs and tasks on the one hand, and giving them powerful digital tools that increase their productivity, the quality and impact of their work, and also how rewarding the work is.

We need incentives in the AI tool development process that tilt things towards the augmentation direction.

Does AI have the potential to change the way we measure value and productivity? If so, how?

Measurement is a big issue. The general answer is yes, because AI systems are, among other things, super-human at pattern recognition. It is easy to see that this power can be used to measure performance in real time much more accurately. This is evident in the expanding use of AI to manage and forecast complex systems: supply chains, smart grids, weather, and so on.

What role can global digital policies play in shaping an AI economy that is fair, and sustainable.

Global digital policy forums, such as those in the United Nations, have a key role to play in identifying blockages and risks associated with AI diffusion. To me, the key thing is diffusion of beneficial technology.

There are some areas where international agreements are needed – treaties, if you like – to try to avoid the most destructive uses of AI: in areas such as autonomous weapons and cyber security.

And what role can universities such as MBZUAI play in developing this economy?

Universities are the places where new ideas develop without constraints coming from commercial or other interests. It plays an essential role in modernizing societies.

As the first university dedicated to AI, MBZUAI has a crucial role to play in developing the science, technology, ethics, policy and vision related to AI.

Finally, last year’s Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry were awarded for work associated with AI. Do you expect to see more Nobel recognition for AI-related research in the coming years? And do you think we might ever reach the point where an AI model itself (not its creators) is awarded a Nobel Prize for discoveries it produces independently?

In a way, yes. I think we will see awards in the sciences to individuals who have done path-breaking work, and often that work will have been enabled or advanced with powerful AI systems. So, it will be more recognition of AI indirectly, because of its role in accelerating scientific research: the prizes will be awarded for the research, not the tools used to achieve it.

I doubt very much if an AI will be the recipient, but I can imagine that an award would go to an individual or group that develops a particularly powerful new AI, or a particularly innovative application.

- Undergraduate ,

- Economy ,

- economics ,

- guest lecture ,

- guest talk ,

- Nobel Prize ,

- governance ,

- digital policy ,

Related

MBZUAI's Launch Lab equips alumni and students with practical startup tools

The six-week pilot program brought alumni and students together to turn early startup ideas into tangible ventures.

- alumni relations ,

- launch lab ,

- startups ,

- alumni ,

- entrepreneurship ,

Designing the human side of AI

MBZUAI’s inaugural HCI Symposium explored how people will live and work alongside AI, and how to ensure.....

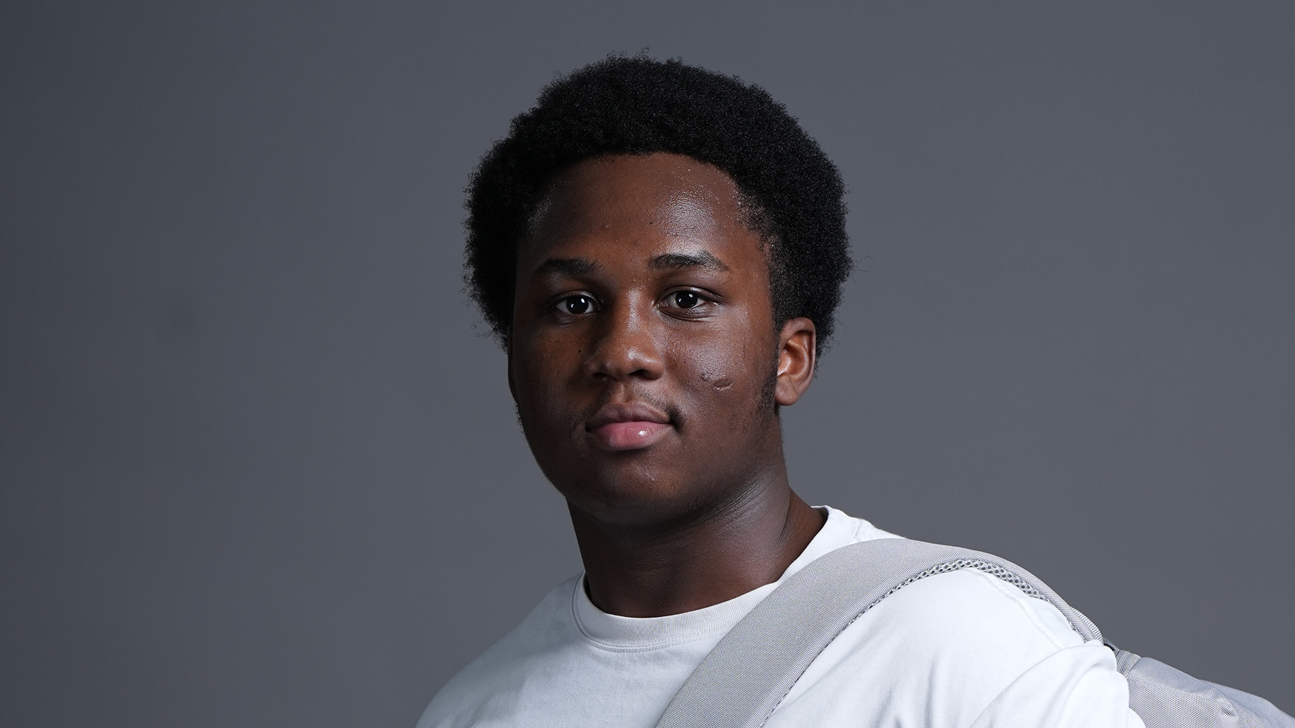

Read MoreYoungest MBZUAI student sets sights on AI superintelligence at just 17

Brandon Adebayo joined the University’s inaugural undergraduate cohort, driven by a passion for reasoning, research, and the.....

- Undergraduate ,

- student ,

- engineering ,