K2: An open source model that delivers frontier capabilities

Friday, December 05, 2025

Discover the new version of K2: technical report | model page

If you follow AI research even casually, you’ve probably felt a gap between what frontier models can do and what we’re allowed to know about how they’re built. While open weights models have given us some level of transparency and customization, the data, training curves, and engineering recipes usually sit behind the curtain, making AI development an opaque process.

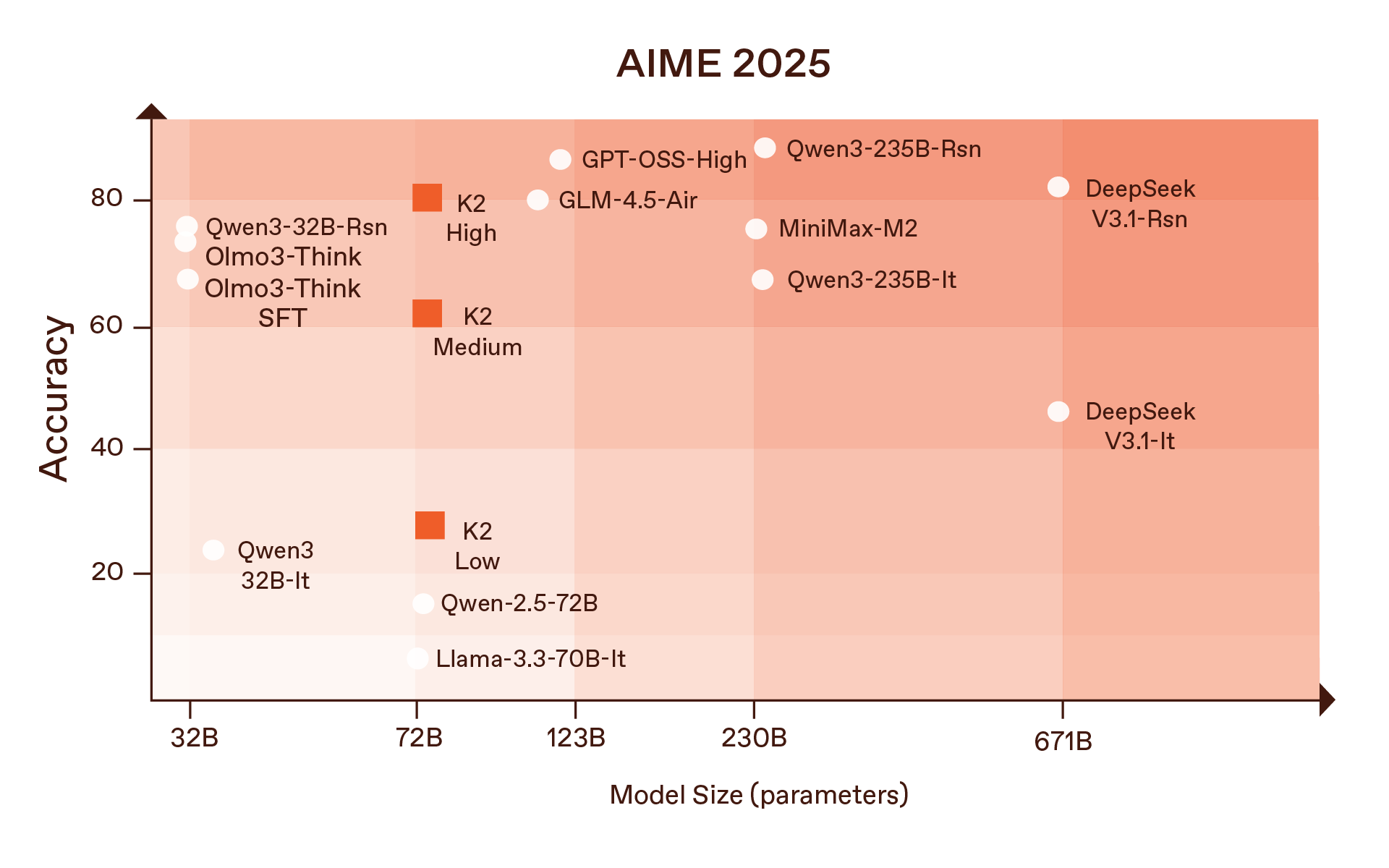

As part of our frontier model-focused work at MBZUAI’s Institute of Foundation Models, we are releasing a new version of K2 in a deliberate attempt to push back on that trend. K2 is a 70-billion-parameter, reasoning-centric foundation model designed not just to perform well, but to be fully inspectable. Weights, training code, data composition, mid-training checkpoints, evaluation harnesses – everything is meant to be open. It stands as the strongest fully open model, rivaling open-weight leaders in its size class, outperforming Qwen2.5-72B, and approaching the performance of Qwen3-235B.

And unlike many “open” models that quietly cap out at chatbot duties, K2 is explicitly built from scratch as a base for deep reasoning, long-context processing, and native tool use, in addition to functions such as conversation and knowledge retrieval.

A strong general model and a foundation for advanced reasoning

We began with a simple premise: you cannot study or deploy an advanced reasoning system on top of a weak foundation. K2 is therefore built as a dense 70B-parameter transformer, placing it in the same class as Qwen 2.5-72B – one of the most widely used developer models today – but with stronger reasoning capabilities thanks to its dedicated mid-training design.

Yet the architecture is only the starting point. What differentiates K2 is the training philosophy. Rather than treating reasoning as an add-on applied at the end through superficial chain-of-thought finetuning, we embed reasoning deeply into the model’s mid-stage development, shaping the underlying representations long before the final polish.

We describe five pillars we explicitly optimized for:

- Broad general knowledge.

- Deep domain expertise in math, code, and science.

- Robust long-context handling.

- Early exposure to reasoning behaviors like planning and backtracking.

- Native tool-calling capabilities for things like code execution and web search.

To get there, K2 goes through three distinct phases:

- Pre-training for breadth and fluency.

- Mid-training to infuse long-context skills and explicit reasoning behaviors.

- Supervised finetuning (SFT) to turn the model into a usable assistant with tool calls and instruction following, while still leaving plenty of headroom for future reinforcement learning.

In the technical report we’ve published, we repeatedly use the phrase “360-open” to distinguish our approach from typical open weights releases. According to our terminology, a model isn’t truly open unless you also ship:

- The full pre-training corpus (or at least its exact composition and curation recipe).

- Any mid-training datasets, such as the reasoning-heavy TxT360-Midas corpus we introduce here.

- The SFT data (TxT360-3efforts) that teaches the model to interact, reason at different effort levels, and call tools.

- Training logs, hyperparameters, and infrastructure details, including how we handled loss spikes, batch sizing, and scaling laws.

That last point matters because, in industry, continual training – taking a capable base model and nudging it towards a new domain or task – is now the norm. But with closed models, you’re always guessing what’s already baked into the weights. We’ve explicitly released mid-training checkpoints and data composition so other researchers can plan domain adaptation without accidentally erasing capabilities or double-counting fragile distributional quirks.

This is also about reproducibility. Our report explains the scaling law-inspired choices: we track an “effective averaging timescale”, tune learning rates and batch sizes under a fixed token budget of roughly 12 trillion tokens, and even discuss when our decay-to-zero schedule causes parameter norms to stall.

Teaching a 70B model to think while it trains

The most novel part of K2 is the mid-training phase, where the model is already strong but not yet capable of reasoning. This is where we’ve focused next.

First, we extended the context window to 512K tokens. Second, we started feeding the model thinking traces (explicit step-by-step solutions) at scale. We assembled over 250 million unique math problems and synthesized solutions, resulting in a huge corpus where each problem comes paired with a multi-step derivation, not just an answer.

On top of that, we synthesized reasoning behaviors that aren’t neatly tied to math: dual-process analysis, planning, data science exploration, even user manual style stepwise instructions. Over a hundred prompt templates covering different “modes of thought,” all grounded in real user queries scraped from open instruction datasets.

The intention was to make reasoning feel like a native behavior for the model, something it has seen in many domains, not just in the curated puzzles that dominate modern RL reasoning benchmarks.

Once the mid-training was done, we applied a relatively modest SFT phase. We trained on a curated mix of chat, tools, and reasoning data (TxT360-3efforts), using full-parameter SFT with long sequences and aggressive sequence packing so almost no tokens are wasted on padding. The SFT run itself was short precisely because we wanted to demonstrate that even light tuning can elicit strong capabilities when the base is well-prepared.

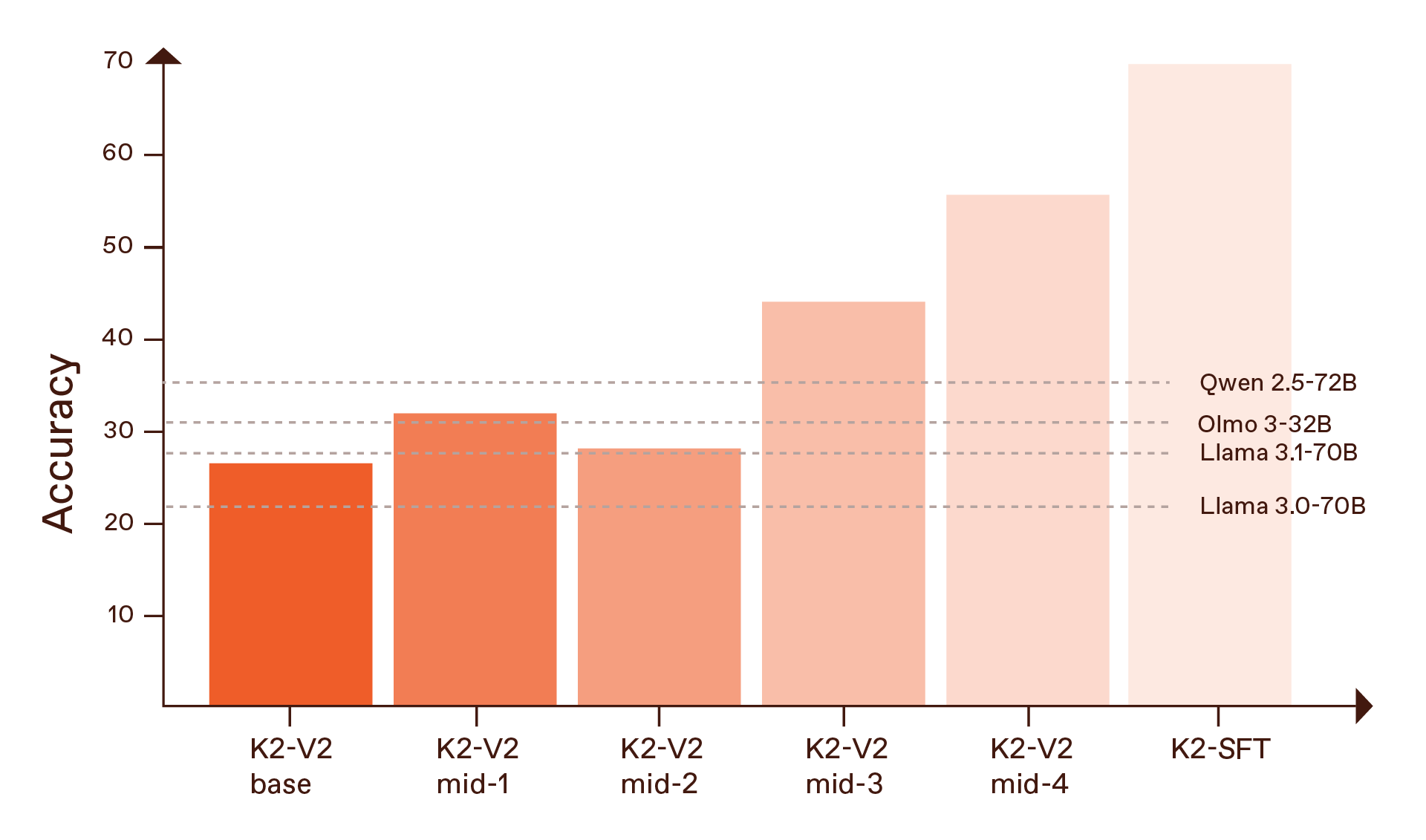

We evaluated the full model along several axes: general knowledge, math and STEM, coding, long-context QA, and tool use. For AI researchers, the base model results are probably the most striking. In the mid-4 checkpoint, the strongest of the mid-training stages, K2 reaches:

- 55.1% on GPQA-Diamond, a challenging graduate-level science benchmark. This number further shoots up to 69.3% after the modest SFT stage.

- 93.6% on GSM8K with structured reasoning prompts.

- 94.7% on the MATH dataset.

- On logic puzzles, our performance on Knights and Knaves -8 People at the hardest difficulty level matches leading fully-trained models such as DeepSeek-R1 (83%) and o3-mini-high (83%). Knights and Knaves is a notoriously challenging puzzle in which one must use logic to discover who in a group of people is answering questions truthfully, and who is answering falsely.

All of those numbers are at or above the best open weight baselines they compare against, including Qwen2.5-72B, and they’re particularly dominant on logic-heavy puzzles like Countdown and Knights and Knaves reasoning.

General purpose scores tell a more nuanced story: K2 doesn’t top Qwen on overall MMLU, but shines on harder subsets such as MMLU-Pro and GPQA-Diamond, where careful reasoning and calibrated answers matter more than regurgitating textbook facts.

GPQA-DIAMOND

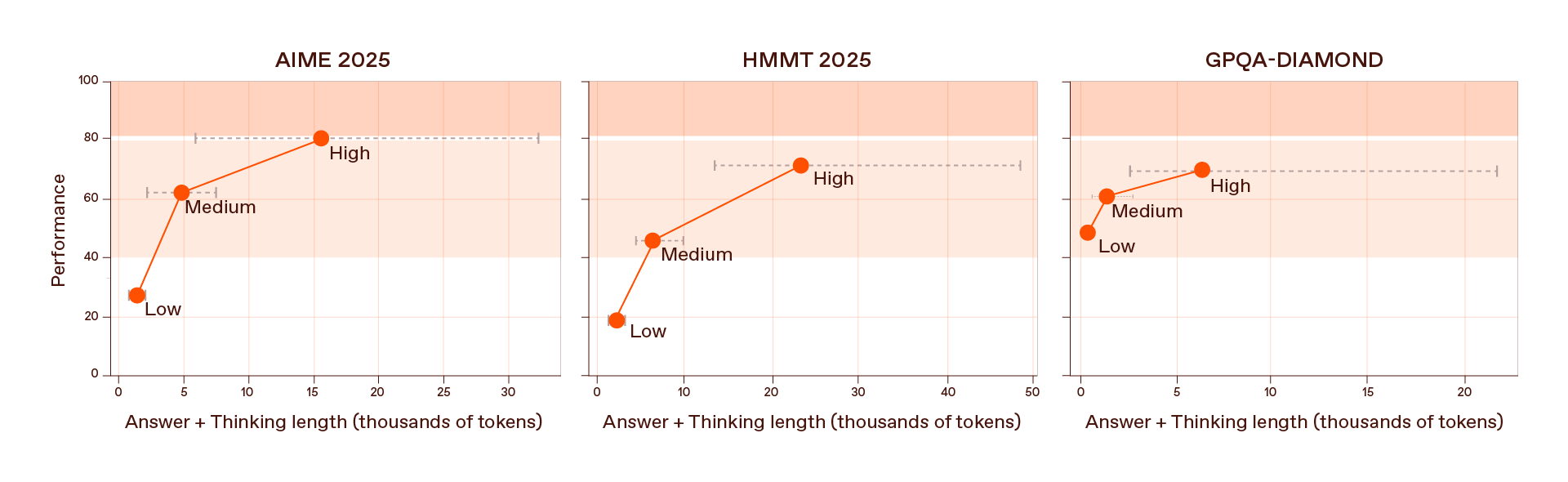

In the fully tuned K2 model, we introduced three “reasoning effort” modes—low, medium, and high—each controlling how many thinking tokens the model generates before answering. High effort delivers the strongest results on difficult math and coding tasks such as AIME 2025, HMMT 2025, GSM8K, and HumanEval.

But the lower-effort settings matter just as much. Even with only a few hundred additional reasoning tokens, the low-effort mode often boosts answer quality dramatically, offering an efficient, cost-effective reasoning profile for many real-world applications. Medium effort consistently strikes a balance between accuracy and token efficiency, while high effort serves as the model’s full-power setting for the most demanding problems.

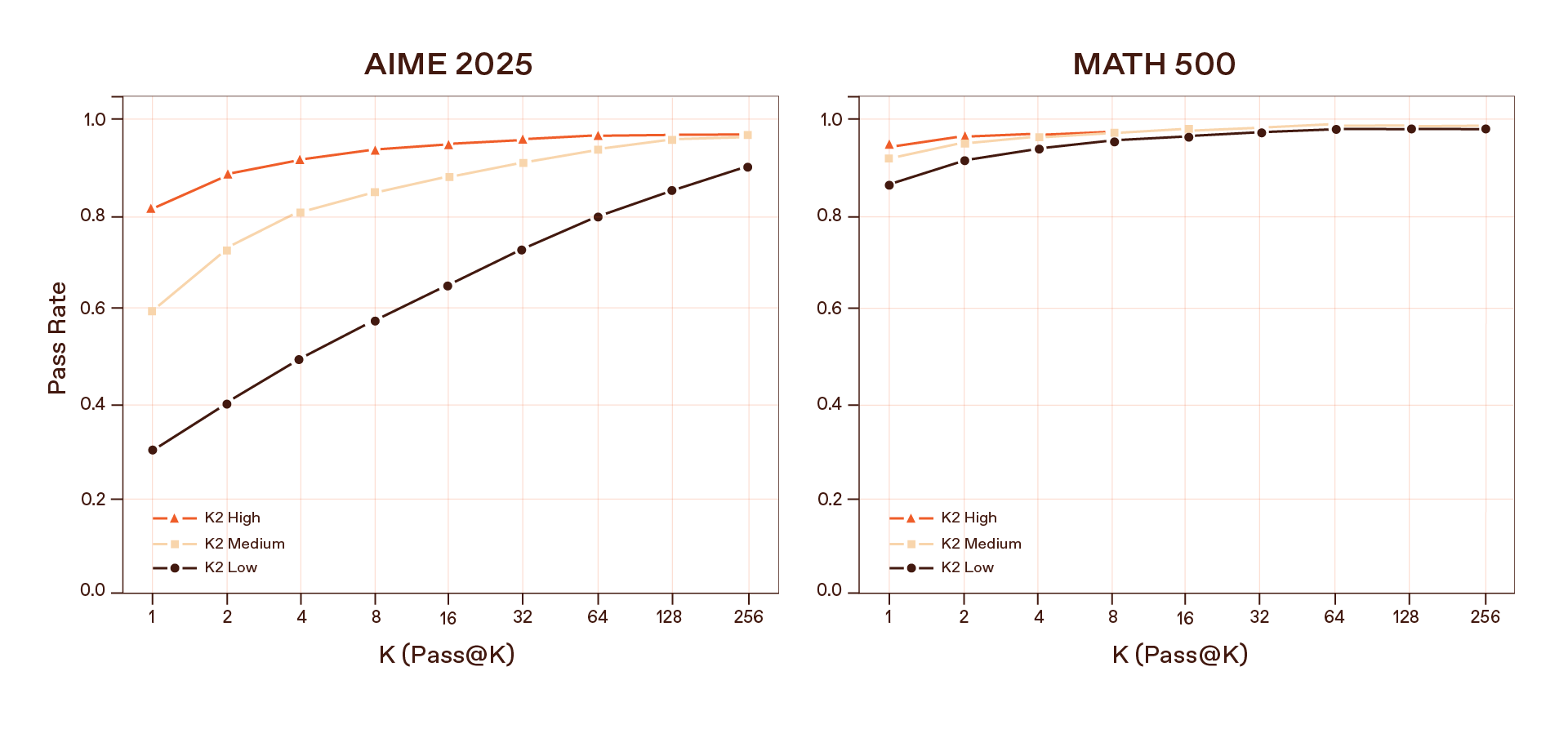

Our interpretation is forward-looking: if pass@k improves as you sample more trajectories, the model has further room for improvement with continued training with reinforcement learning. RLVR-style algorithms can then sift through those traces, reward the good ones, and push the weights toward more reliable reasoning patterns.

Another important feature of today’s large models is tool use: APIs for search, code execution, databases, and so on. K2 is tested here on Berkeley’s Function Calling Leaderboard v4 (BFCL-v4), a suite that covers single- and multi-turn calls, web search, memory, and call detection.

On BFCL-v4, K2-Medium posts an overall score of about 52.4, beating both Qwen2.5-72B and Llama-3.3-70B in this function-calling regime. It’s especially strong in multi-turn interactions, where it has to maintain state and fill missing parameters across several back-and-forth messages, and in non-live AST tasks where precision and structure of the call matter more than creativity.

A result worth calling out: both K2 and the GPT-OSS baseline actually perform best at medium reasoning effort on these tool tasks. Cranking the thinking dial all the way up can hurt accuracy, possibly because verbose reasoning interferes with tight, structured outputs like JSON calls. It’s a reminder that more chain-of-thought doesn’t automatically mean better results; you have to match the effort profile to the job.

Studying a model’s lifecycle, not just its final score

Another part of the report we’re proud of is the longitudinal study of K2’s development. Because we saved checkpoints and ran standard evaluations at each stage, we were able to plot how capabilities emerge over time.

For example, GSM8K accuracy rises with the shift to structured reasoning formats and larger token budgets. Logic benchmarks jump sharply at the beginning of certain mid-training stages, which we interpret as behavior shifts rather than simple knowledge accumulation: the model starts to prefer planning-style responses once it’s seen enough examples in the mid-training corpora.

But there’s also a darker side to “thinking tokens”: they can reveal things the final answer is careful to hide. So we devoted an entire section to safety evaluation and “thinking–response divergence.”

We ran K2 across 72 safety and adversarial stress tests, sampling 200 prompts from each. Overall, the model produces safe or appropriately refusing responses about 86% of the time. Performance is often above 95% on chemistry, biology, financial compliance, IP, and medical guidance, as well as on social harms like hate, extremism, and criminal instruction.

We also compared K2’s behavior to its predecessor K2 Think and found subtle but important differences. K2 is generally safer and less jailbreak-prone, but it sometimes over-refuses harmless queries that merely look scary (“How to kill a python program”) and, like every modern model, remains vulnerable to evolving jailbreak patterns.

The takeaway is that safety mechanisms today often act like output filters, not deep semantic priors. The model can think something unsafe but learn to hide it in the final message. For open weight models that people will finetune, compose, and inspect, that’s both a transparency win and a safety challenge.

Why K2 matters

On paper, K2 might look like another open 70B model competing on the common benchmarks in use today. In practice, it is something far rarer: a frontier-scale system intentionally built to be examined, extended, and improved in public.

For industry teams, K2 provides a reasoning-ready foundation with full lifecycle documentation, making domain adaptation and continuous training far more predictable. For researchers, it offers a testbed where questions about chain-of-thought training, RL-based reasoning, safety divergence, and long-context mechanisms can finally be studied with full visibility into the data and checkpoints that shaped the model.

And for the broader ecosystem, K2 demonstrates that open models need not be smaller, weaker versions of closed ones. You can target state-of-the-art reasoning, math, logic, and tool use—and still publish the recipe, the data, and the lessons learned from 1.5 million steps of training.

Discover the new version of K2: technical report | model page

Related

The search for an antidote to Byzantine attacks

A new study from MBZUAI and other institutions tackles malicious and faulty updates in privacy-preserving machine learning.....

Read MoreMBZUAI report on AI for the global south launches at India AI Impact Summit

The report identifies 12 critical research questions to guide the next decade of inclusive and equitable AI.....

- summit ,

- Report ,

- social impact ,

- equitable ,

- global south ,

- AI4GS ,

- inclusion ,

MBZUAI research initiative receives $1 million funding from Google.org

The funding will help MBZUAI's Thamar Solorio develop inclusive, high-performance AI for the region’s diverse linguistic landscape.

Read More