Inside the 2025 International Olympiad of AI: the rules, the rationale, and what comes next

Monday, September 08, 2025

The International Olympiad in AI (IOAI) is a new competition involving high school students from around the world racing to build the best natural language processing, computer vision and robotics systems. Think of it as the Olympic Games of Artificial Intelligence.

Modeled after some of the most famous International Science Olympiads – including the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) and the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) – IOAI aims to find and celebrate the next superstars in AI. And in 2026, the event will come to Abu Dhabi for the first time in 2026 – hosted by MBZUAI.

Having sponsored the 2024 and 2025 editions, MBZUAI has a long-standing association with the global competition. Two of the University’s faculty – Assistant Professor of Natural Language Processing, Yova Kementchedjhieva, and Assistant Professor of Machine Learning, Maxim Panov – are also members of IOAI’s International Scientific Committee (ISC), and have been instrumental in bringing the 2026 event to the UAE.

How IOAI works

IOAI 2025 took place in Beijing in August and ran three parallel competitions: the Individual Contest, the Team Challenge, and GAITE (Global AI Talent Empowerment). Only the Individual Contest determined medals; Team Challenge and GAITE offered separate awards. According to the official rules, participants had to be under 20 on Individual Day 1 and enrolled in a high school in the country they represent.

The competition took place over a week and demanded a lot from participants. Before the competition started proper, students warmed up with an at-home round consisting of three problems scored only for practice. In Beijing, proceedings began with a 1.5-hour practice session, followed by two six-hour Individual Contest days. The first day extended the at-home tasks, then day two introduced entirely new ones. According to Kementchedjhieva and Panov, the second day was intentionally designed to be tougher, as it had leaner AI assistant budgets and unfamiliar domains which resulted in a higher bar for generalization.

One of the early challenges in organizing this year’s edition was aligning the ISC and the scientific committee of the host country. The ISC oversees, advises and recommends but the host country has to actually deliver the event on the ground, set up the machines, the cloud infrastructure and the contest platform. As the IOAI is only two years old, there are still no standards in terms of exactly how things should be done and each location comes with its own constraints. Kementchedjhieva and Panov explain that they learned a lot this year about how to collaborate more efficiently with host countries and what feedback is needed at every stage to ensure that once everyone is on site and ready to compete, everything is set up in the best way possible.

Everyone competed on identical local machines with identical GPU resources (≥24 GB RAM). Tasks were delivered, solutions submitted, and provisional scores viewed through Bohrium, a web-based Jupyter environment from DP Technology with VS Code/PyCharm installed locally. TensorFlow/Keras were not available; PyTorch/scikit-learn and friends were. Access to the internet was also blocked, except for a short whitelist (docs for PyTorch, scikit-learn, Hugging Face, NumPy, Python, PyPI, plus a translation site). Students had access to an integrated GPT-4oi assistant, which had a per-query token cap.

In practice, those constraints shaped the problems. “The host initially was prepared to provide only smaller, older GPUs,” Panov says, but after the ISC team pushed back, capacity improved, enabling more interesting tasks while staying away from brute-force large model training. The goal: test creativity and understanding, not who can grind the biggest transformer.

Kementchedjhieva adds that the AI assistant was meant for docs look-ups, debugging, and explanations, not end-to-end solve-my-task prompts. “We set the model to GPT-4o-mini… to avoid participants trying to ask the AI assistant to fully solve the task.”

Rules, scores, and on-the-ground challenges

Every task was scored out of 100 points via normalization: your raw metric (say accuracy or AUC) was mapped between a baseline (“Min_Score”) and the higher of 0.9×the Scientific Committee solution or the best contestant submission (“Max_Score”). That keeps tasks comparable and rewards improvement over baseline while avoiding distortions if a metric’s raw range is odd.

During the contest, each participant saw only their own provisional scores (per subtask) and the current best raw score achieved by anyone; a validation Leaderboard A was displayed publicly outside the hall but hidden from contestants to curb overfitting and avoid morale swings mid-event. “It gave a sense of the ceiling without discouraging students with a live rank,” Kementchedjhieva says.

For non-English teams, the organizers provided a three-hour translation session before each contest day. Team Leaders (TLs) worked on host-provided laptops with a translation website; GPT-4 pre-translations were there for unsupported languages too. To avoid any issues, TLs had to sign an NDA and were under quarantine from the start of translation until the contest began; no phones, no personal laptops. Afterward, all translations were shared publicly to audit against hints or unequal information.

In the team challenge, appeals were filed only by TLs, opened right after each contest and were due within one hour after its round ended. The International Jury reviewed cases and reported decisions to the General Assembly. Cheating (system tampering, unauthorized comms, prohibited devices) could have led to disqualification, and the committee caught a bathroom-break chat between two contestants who were penalized. “Phones, earphones, etc. were not allowed in the hall,” Panov notes.

The Team Challenge flipped the script: one team, shared seats, open collaboration, tools and web access defined per task. This year’s brief revolved around controlling a humanoid robot in simulation, forcing divisions of labor and parallelization, closer to systems building than leaderboard sniping. In order to make the competition more accessible for countries with limited expertise in computer science, the ISC team introduced a simplified parallel contest this year called GAITE where participants were given extra hints and easier tasks. “GAITE offers a gateway for participants from countries that are not on the AI map,” says Kementchedjhieva. “Thankfully, we had 16 GAITE participants from four countries, and we hope to grow that number next year.”

Kementchedjhieva and Panov confess that dealing with live infrastructure was at times hard. During the first day, Bohrium’s network briefly buckled, delaying job queues and forcing an extension; luckily, the second day ran smoothly after fixes. That’s the sort of behind-the-scenes volatility rules can’t fully prevent but tight monitoring and contingency time helps.

The combination of identical hardware, a constrained software stack, a limited AI assistant, and post-hoc normalization tried to keep the contest about ideas, modeling trade-offs, and disciplined iteration. It also provided a hedge against the “just-ask-the-LLM” temptation that would render competition meaningless and against resource gaps between teams.

IOAI’s third edition lands in Abu Dhabi and MBZUAI at the start of August in 2026. The committee is already moving to a less intense schedule, earlier task testing and copy-editing, and, crucially, tighter network policies: for example, zero internet access except for an AI assistant. MBZUAI will also drive a fresh review of compute provisioning.

Related

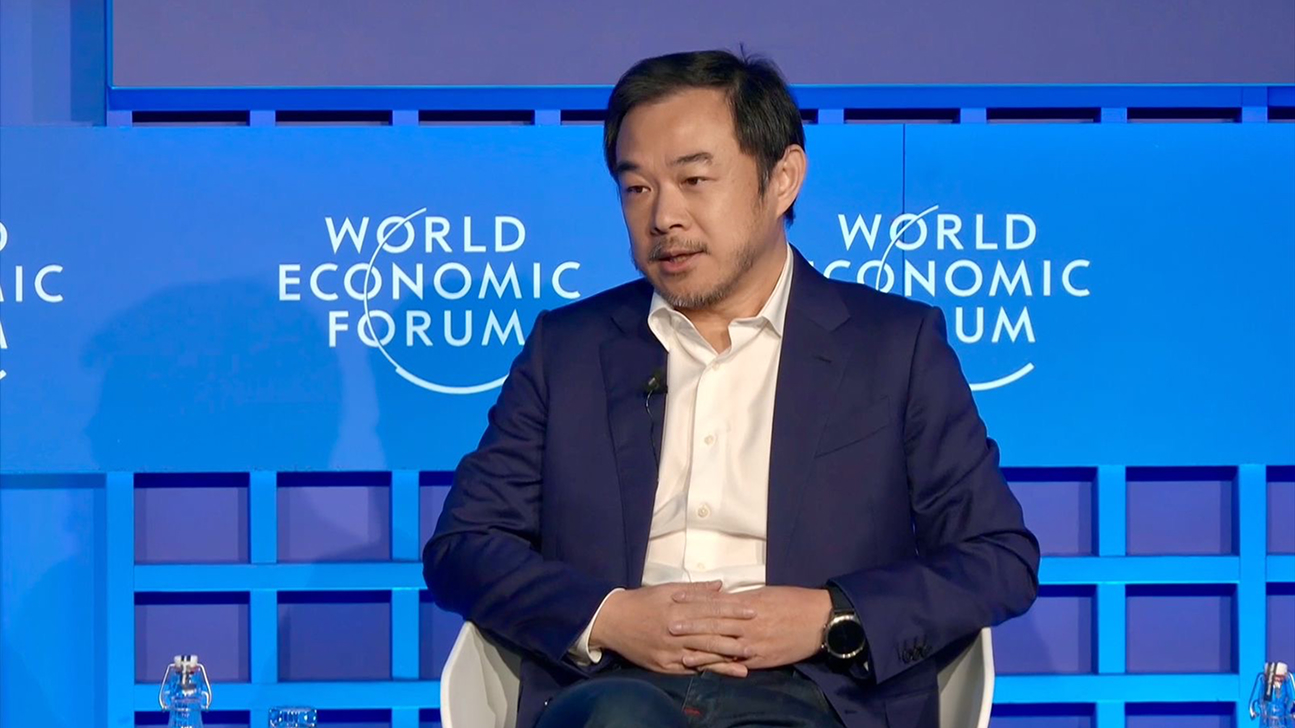

Eric Xing explores the ‘next phase of intelligence’ at Davos

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, MBZUAI President and University Professor Eric Xing looked ahead.....

- Davos ,

- WEF ,

- panel ,

- intelligence ,

- Eric Xing ,

- foundation models ,

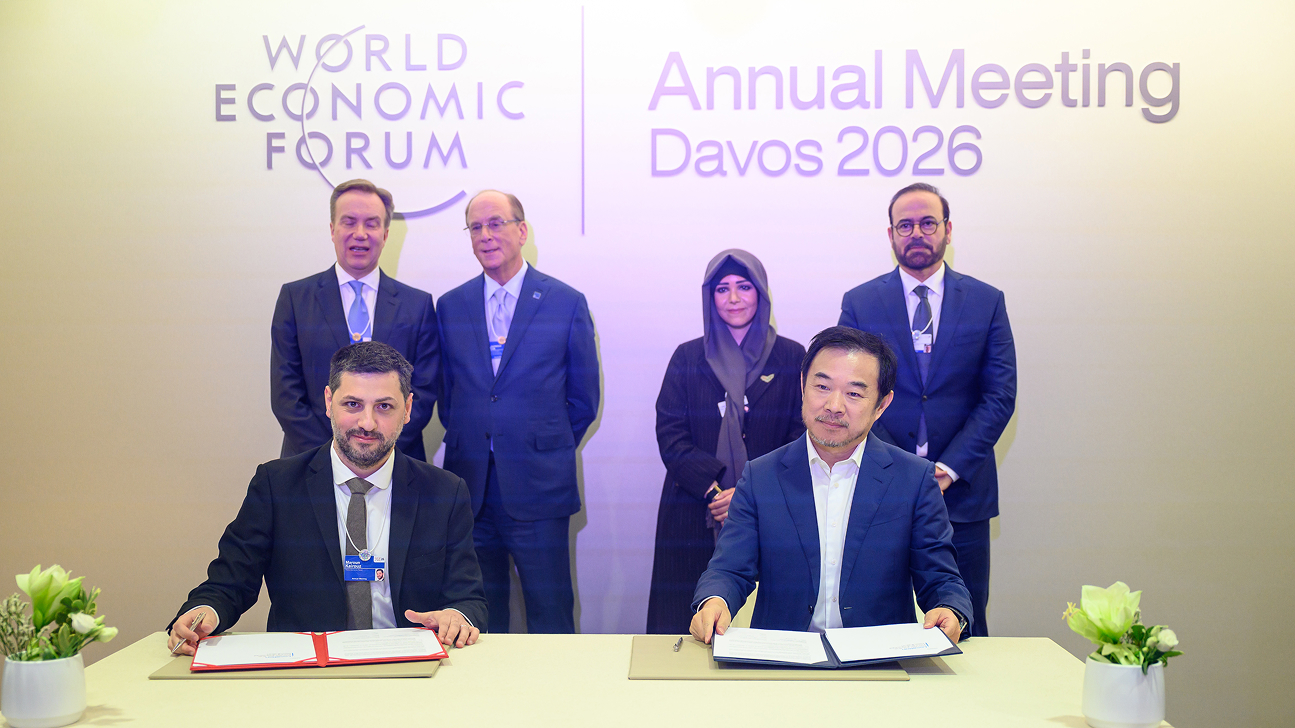

MBZUAI signs agreement with World Economic Forum as Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution (C4IR)

MBZUAI will launch the Centre for Intelligent Future as a global platform – connecting AI research with.....

- WEF ,

- humanity ,

- economic ,

- social ,

- World Economic Forum ,

- partnership ,

MBZUAI's Launch Lab equips alumni and students with practical startup tools

The six-week pilot program brought alumni and students together to turn early startup ideas into tangible ventures.

- launch lab ,

- alumni relations ,

- startups ,

- alumni ,

- entrepreneurship ,