Why 3D spatial reasoning still trips up today’s AI systems

Friday, December 05, 2025

Ask a vision-language model to “find the red mug” in a photo and it’ll perform well. Ask it to “grab the mug to your left while you’re facing the whiteboard,” and the wheels come off. That gap between naming things and understanding where they are relative to you and other objects is exactly what a new NeurIPS 2025 paper from MBZUAI sets out to measure.

The team, which includes Ph.D. students Jiaxin Huang and Ziwen Li, and research associate Hanlue Zhang, introduces SURPRISE3D, a large benchmark that forces models to ground language in the geometry of real indoor scenes, which they pair with a task they call 3D Spatial Reasoning Segmentation (3D-SRS). The main finding of the paper is that even the best 3D vision-language systems stumble badly once you take away category names and demand genuine spatial reasoning.

Huang also authored another paper accepted at NeurIPS called MLLM-For3D which serves as a companion to SURPRISE3D. While SURPRISE3D introduces the benchmark and task definition, MLLM-For3D explores how 2D multimodal large language models can be adapted for 3D reasoning segmentation.

Even though “spatial reasoning” might sound abstract, in practice it’s the stuff embodied AI needs in order to function: understanding phrases like “the chair behind the sofa,” parsing egocentric instructions such as “on your right,” and picking out the closest or furthest object among many look-alikes.

“We realized that most 3D vision-language benchmarks reward models for memorizing object names rather than understanding spatial relations,” says Huang. “To build embodied AI that can follow natural human instructions, we needed a dataset that forces models to reason about geometry, perspective, and spatial context, not just vocabulary. After all, we live in a 3D physical world, and the core question is: How do humans engage with it? This research was driven by the desire to help AI systems develop the same intuitive spatial understanding that people use every day. Our goal with SURPRISE3D is to help machines begin building such mental models of the 3D world, so they can see, reason, and act more like us.”

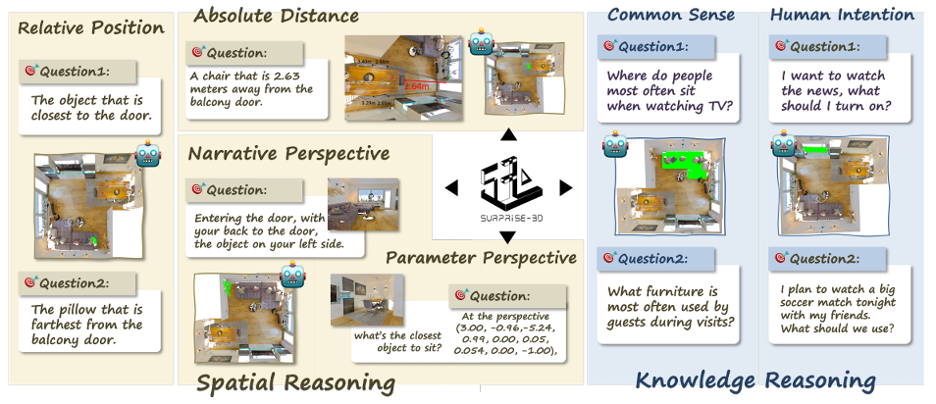

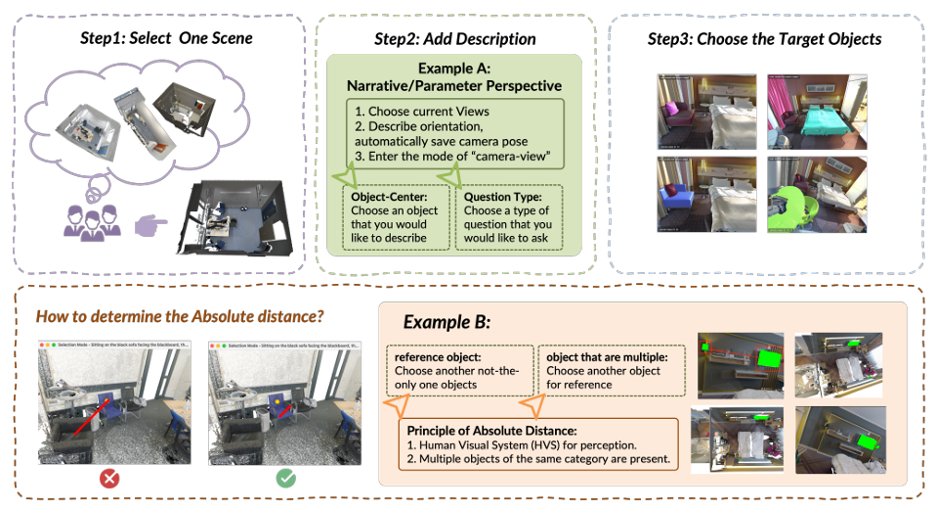

SURPRISE3D builds this into the evaluation from the ground up. It spans 900+ indoor scenes and contributes 200,000+ pairs of language queries and 3D masks, covering 2,800+ object classes. Crucially, more than 89,000 of those queries were written by humans to avoid naming the target object so shortcuts won’t save you. Models must trace relationships, perspective, and distance to find the right instance, not just latch onto a class label. The benchmark also adds 110,000 knowledge-centric queries about common sense and human intention (“the object used to sit,” “what someone might reach for”), but its beating heart is the spatial suite.

Removing crutches and raising the bar

The work is motivated by a simple critique: most 3D vision-language datasets let models “win” by reading object names. Replace those names with placeholders like “object,” and performance falls off a cliff: evidence of shortcut bias rather than real understanding. SURPRISE3D deliberately strips those crutches away and organizes spatial reasoning into four families: relative position (“left of the cabinet,” “behind the sofa”), narrative perspective (egocentric instructions from a described point of view), parametric perspective (camera pose specified numerically), and absolute distance (superlatives like “closest” or explicit distances). The target isn’t a loose bounding box, but a segmentation mask over the 3D scene, which forces precise grounding. If multiple objects satisfy the query, the mask must include all of them. That combination of implicit language, viewpoint awareness, and fine-grained masks raises the bar from “roughly the right stuff” to “exactly the right thing.”

To make this a living standard for comparison, the authors define 3D-SRS: ‘given a 3D scene and a query, return the mask of the referred object(s)’. They evaluate with mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU) and “accuracy” at IoU thresholds, and they slice results by reasoning type so you can see where models crack. The baseline roster includes several strong 3D vision–language methods (MLLMfor3D, 3D-Vista, Reason3D, Intent3D, and ChatScene) tested both in zero-shot settings and after fine-tuning on SURPRISE3D.

The zero-shot numbers tell a consistent story: spatial reasoning is where even some of the best models go to die. Averaging across methods and task types, overall accuracy at IoU-0.25 lands around 8.3%, at IoU-0.50 around 5.2%. Knowledge questions (common-sense and intention) fare better (still low, but comparatively less grim) while narrative and parametric perspective are the worst of the lot. In some sub-tracks, methods collapse to near zero once object names are absent. That’s a direct refutation of the idea that today’s 3D-LLMs have learned “spatial intelligence” as a side effect of scale. They haven’t, at least not in a way that survives shortcut removal.

Fine-tuning on SURPRISE3D helps but not enough to declare victory. The biggest relative gains arrive in the “easier” spatial categories like relative position; the most fragile remain perspective-taking and absolute distance, where even tuned models struggle to simulate a narrator’s viewpoint or compare multiple instances cleanly.

What makes these cases so hard? The failure modes look a lot like what you see in robots that almost work. For egocentric instructions, models need to bind “left” and “right” to a specific viewpoint, not some canonical room axis, a capability most current architectures don’t encode explicitly. For absolute distance, they must enumerate candidate instances and compare 3D distances or superlatives (“closest to the bed”), which demands geometry-aware reasoning rather than text matching. For relative position under occlusion, they must reason in true 3D, not from a single rendered view, to find “behind the sofa” when the target is partially hidden. SURPRISE3D forces all three at once, and it rewards only the method that gets the exact objects, not just the class. The result is an evaluation that penalizes hand-wavy grounding and exposes where “vision–language understanding” ends and spatial intelligence begins.

Huang says that they were surprised by how fast performance collapsed once they removed object names.

“Even large multimodal models that look strong in zero-shot tests failed almost completely on spatial reasoning, sometimes down to near-zero accuracy,” she says. “During our earlier work on MLLM-For3D, we realized that current 3D-Large language model or vision-language models lack a clear scaling law, largely because existing datasets fail to capture spatial reasoning. At the same time, we found that today’s large language and multimodal models still lack the intrinsic ability for spatial reasoning. That’s why we decided to rely on human-written queries in SURPRISE3D, to explicitly encode human spatial understanding and eliminate the shortcuts that models typically exploit. By doing so, the dataset exposes the genuine reasoning gaps that current architectures cannot mask with memorization.”

The importance of coverage and supervision

The authors also situate SURPRISE3D in a crowded landscape of 3D datasets and show why coverage and supervision matter. Compared with classics like ScanRefer and ReferIt3D, which rely on named categories and 3D boxes, SURPRISE3D pushes toward name-free queries and mask-level precision. Relative to newer efforts like ScanReason, Reason3D, and Intent3D, it expands the reasoning taxonomy and adds a disciplined treatment of perspective which prior work lacked. A comparison table in the paper makes the pattern plain: most datasets lean on explicit names, templates, or shallow relations; SURPRISE3D is built to break those habits.

If you’re designing 3D-aware language models, you’ll need egocentric priors and pose-aware encodings so that “to your left” is grounded in a concrete frame, not guessed. You’ll need multi-view or 3D-native aggregation to cope with occlusion and viewpoint shifts. And you’ll need set-reasoning over instances rather than hoping a transformer will infer metric geometry from text alone. The paper points to these directions directly, suggesting dynamic pose embeddings and multi-view reasoning as promising fixes for the worst failure modes it uncovers.

In terms of limits, the benchmark is currently indoor-only and inherits ScanNet++’s domain; parametric viewpoint queries, while rigorous, can feel less natural than human-written egocentric descriptions; and the human annotation that gives the spatial queries their bite doesn’t scale infinitely. But the value of SURPRISE3D is precisely in its discipline: implicit, perspective-aware language; object-name avoidance to kill shortcuts; fine-grained masks; and a taxonomy that maps cleanly onto what robots and AR systems actually need to do. As a measuring stick for embodied AI, it’s much closer to the job.

Thanks to SURPRISE3D, we finally have a benchmark that rewards the right instincts. If your assistant is going to tidy a desk, set a table, or hand you “the screwdriver to your right,” it has to parse space the way people do: by anchoring directions to a viewpoint, comparing like with like, and resolving ambiguity with context, not with a database of names. SURPRISE3D makes those demands explicit and shows, with numbers, where the field stands today and where it has to go next.

If you are interested in following this project, check out the links below for more information:

- Project page: https://mbzuai-liziwen.github.io/Surprise3D/

- GitHub repositories: https://github.com/liziwennba/SURPRISE3D andhttps://github.com/tmllab/2025_NeurIPS_MLLM-For3D

- Hugging Face dataset: https://huggingface.co/datasets/hhllzz/surprise-3d

- research ,

- conference ,

- neurips ,

- benchmark ,

- Vision language model ,

- spatial reasoning ,

- 3D ,

Related

The search for an antidote to Byzantine attacks

A new study from MBZUAI and other institutions tackles malicious and faulty updates in privacy-preserving machine learning.....

Read MoreMBZUAI and Minerva Humanoids announce strategic research partnership to advance humanoid robotics for applications in the energy sector

The partnership will facilitate the development of next-generation humanoid robotics tailored for safety-critical industrial operations.

Read MoreAI and the silver screen: how cinema has imagined intelligent machines

Movies have given audiences countless visions of how artificial intelligence might affect our lives. Here are some.....

- cinema ,

- art ,

- fiction ,

- science fiction ,

- artificial intelligence ,

- AI ,