What reinforcement learning can teach language models about reasoning

Monday, December 01, 2025

An area of debate in AI over the past year or so relates to the role that reinforcement learning plays in the development of reasoning models – language models that can solve complex problems. The concept is straightforward: take a pre-trained language model and use reinforcement learning to teach it how to “think through” difficult problems and arrive at an answer. In short, teach it how to reason.

Some recent analyses have been skeptical of the approach, arguing that reinforcement learning doesn’t actually improve a model’s reasoning ability but simply makes it better at eliciting knowledge that it had already gained during pre-training. The concern is that reinforcement learning isn’t teaching reasoning at all: it’s just reorganizing what the model already knows.

But a study from researchers at the Institute of Foundation Models (IFM) at MBZUAI provides an analysis that is more complex and nuanced.

The team’s findings show that what is typically called “reasoning” in AI is really a collection of domain-specific skills rather than a single transferable ability and models benefit from reinforcement learning in different ways depending on the domain.

For domains that are frequently encountered during pretraining, like math and coding, models improve from cross-domain reinforcement learning, meaning that training on math can improve coding performance. In contrast, for domains like logic and simulations that often aren’t included in pre-training data, models show improvements only when they are specifically trained on those domains. The implication is that reinforcement learning acts as an elicitor for heavily pre-trained domains, while it genuinely teaches new reasoning skills in underrepresented domains.

The team’s work can be used to help inform the development of models that have general reasoning abilities that span a variety of domains, says Zhoujun Cheng, a research intern at IFM, doctoral student at the University of California San Diego, and co-lead author of the study.

Cheng and his colleagues are presenting their findings at the 39th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2025) in San Diego, California.

In addition to Cheng, the authors of the study are Shibo Hao, Tianyang Liu, Fan Zhou, Yutao Xie, Feng Yao, Yuexin Bian, Yonghao Zhuang, Nilabjo Dey, Yuheng Zha, Yi Gu, Kun Zhou, Yuqi Wang, Yuan Li, Richard Fan, Jianshu She, Chengqian Gao, Abulhair Saparov, Haonan Li, Taylor W. Killian, Mikhail Yurochkin, Zhengzhong Liu, Eric P. Xing, and Zhiting Hu.

Will you be my GURU?

To conduct the analysis, the researchers created a dataset called GURU that includes 92,000 examples that span six domains: math, code, science, logic, simulation, and tabular reasoning.

Research has typically focused on math and code to test reasoning partly because these fields offer easily verifiable answers. (You can check if a math solution is correct or if a program generated by a model passes a test.) GURU extends this approach across a much broader range of reasoning tasks, each with domain-specific reward functions that allow for automated verification.

“In general researchers have been satisfied with using math or code datasets because they are available, but by having more data across different domains, we can get more interesting insights,” says Shibo Hao, a research intern at IFM, doctoral student at the University of California San Diego, and co-lead author of the study.

Hao says the team had to overcome significant challenges to create GURU. For example, they had to source the data, deduplicate it, and design domain-specific reward functions. They also had to remove questions that were either too easy or too difficult.

The result is a dataset that makes systematic cross-domain reasoning research possible for the first time.

How reasoning transfers (or doesn’t)

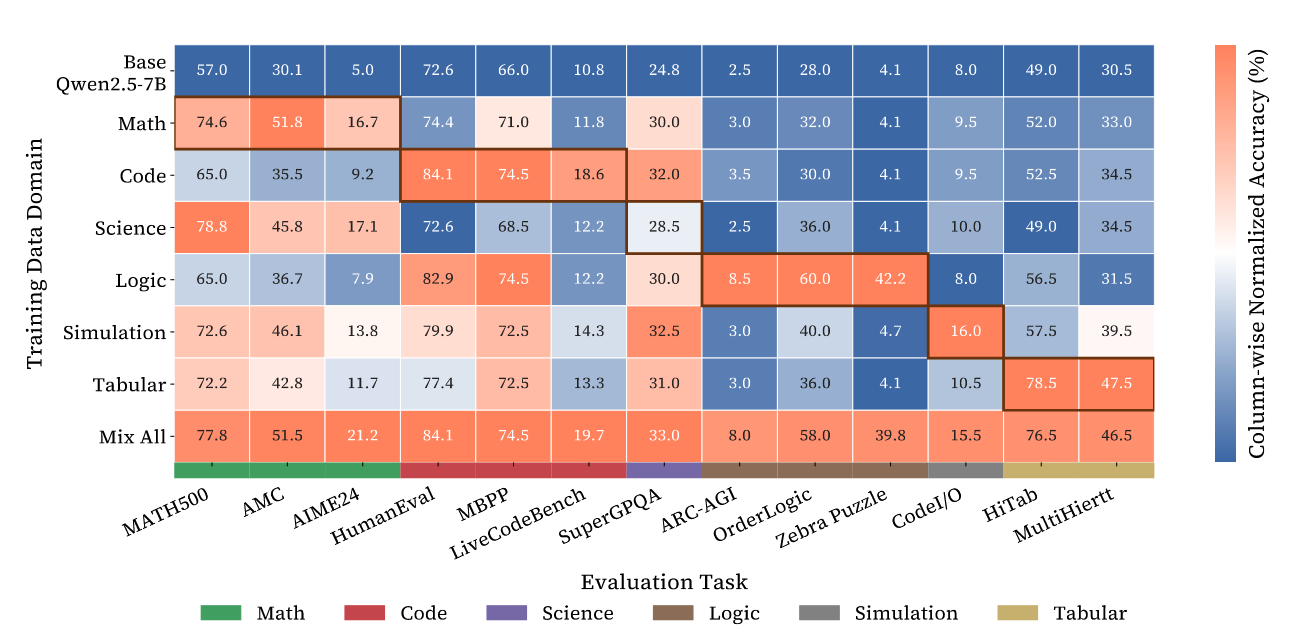

Using GURU, the team trained two models – based on Qwen2.5-7B and 32B – on individual domains and mixed-domain combinations and mapped how reasoning capabilities transfer across them. They started with experiments using 3,000 samples from each domain, training the models on each domain individually and across the six combined. They tested the models on a subset of questions and measured their performance. The results revealed asymmetries in how reinforcement learning influenced performance across the domains.

When the researchers trained models on math problems, performance improved not only on math but also on coding and science. And when they trained on code, the models improved on math and science. The same went for training on science. These three domains formed a cluster of mutually reinforcing skills. The reason lies in the data that was used for model pretraining, as math, code, and science appear frequently. It seems that reinforcement learning in these domains refines and organizes knowledge the model already possesses instead of teaching it new skills.

The patterns were different for the other three domains. The researchers found that training on logic puzzles didn’t improve performance on tabular reasoning. And training on simulation tasks didn’t help with logic. The models only showed improvement in these domains when domain-specific data was used for reinforcement learning, giving the models new, domain-specific capabilities.

“We show that if we do reinforcement-learning training on math we don’t see reasoning improvements on logic,” Cheng says. “We assume that this is because math is heavily pretrained but for logic the model needs to learn from domain-specific reinforcement learning.”

The heatmap shows the performance gains (accuracy) from reinforcement-learning training on different domains (rows) when evaluated on the test sets on different domains (columns). Warmer colors indicate higher performance gains, computed by applying min-max normalization to the validation accuracies within each column. Accuracy is reported using the checkpoint with the highest average score across tasks. Khaki-colored rectangles mark in-domain evaluations (diagonal); others reflect cross-domain generalization.

Overall, they found that their two models (GURU-7B and GURU-32B) achieved state-of-the-art performance among open, reinforcement-learning-trained models, outperforming the best baselines by 7.9% and 6.7% across domains.

The researchers continued their analyses by manipulating the difficulty of training data. When they trained only on hard math problems, in-domain performance improved, which was expected. But performance on easier tasks in other domains got worse. This suggests that the reasoning being learned (or elicited) is tied to the difficulty and structure of the training domain. The practical implication is that a model trained only on competition-level math problems might excel on those difficult questions but struggle with basic ones in other areas.

The team also investigated a more fundamental question: does reinforcement learning teach models to solve new problems or just help them more reliably find solutions they could already reach? To explore this, the researchers conducted Pass@k experiments, which measure whether a correct answer appears in multiple attempts. Recent studies have suggested that reinforcement learning doesn’t expand the set of questions that models can solve but just makes them better at generating correct answers that they could reach with enough tries. The results from this study show that the reality is, again, more nuanced.

For a logic puzzle task, a domain that is not commonly included in pretraining data, GURU was found to expand the reasoning boundary compared to the base models. Model size was also a factor. GURU-7B plateaued at k=32 while GURU-32B continued to rise across the sampled range (up to k=256). This suggests that a stronger base model might more easily uncover new reasoning trajectories through reinforcement learning, they explain.

Implications for general reasoning

Taylor Killian, a senior research scientist at IFM and co-author of the study, says that this was the first time that the differential performance of reinforcement learning across reasoning domains has been studied. “We wanted to start a conversation about how we as a research community need to be careful about what we put into these models and how we study their outputs,” he says.

That said, GURU is more than just a research exercise. The dataset was used in the development of K2 Think, a reasoning model released by IFM earlier this fall.

“We’re using this data to build models that have greater and greater reasoning capabilities,” Killian says. “GURU is the start of this, and it has helped to seed our capabilities from a reinforcement-learning perspective.”

Related

MBZUAI and Minerva Humanoids announce strategic research partnership to advance humanoid robotics for applications in the energy sector

The partnership will facilitate the development of next-generation humanoid robotics tailored for safety-critical industrial operations.

Read MoreMBZUAI launches K2 Think V2: UAE’s fully sovereign, next-generation reasoning system

The 70-billion parameter advanced reasoning system is now built on the K2-V2 base model – the Institute of.....

Read MoreK2 Think V2: a fully sovereign reasoning model

MBZUAI's Institute of Foundation Models has released its first fully sovereign reasoning model with a new version of K2 Think.

- llm ,

- sovereign ,

- reasoning IFM ,

- foundation model ,

- K2 ,

- K2 Think ,

- Institute of Foundation Models ,