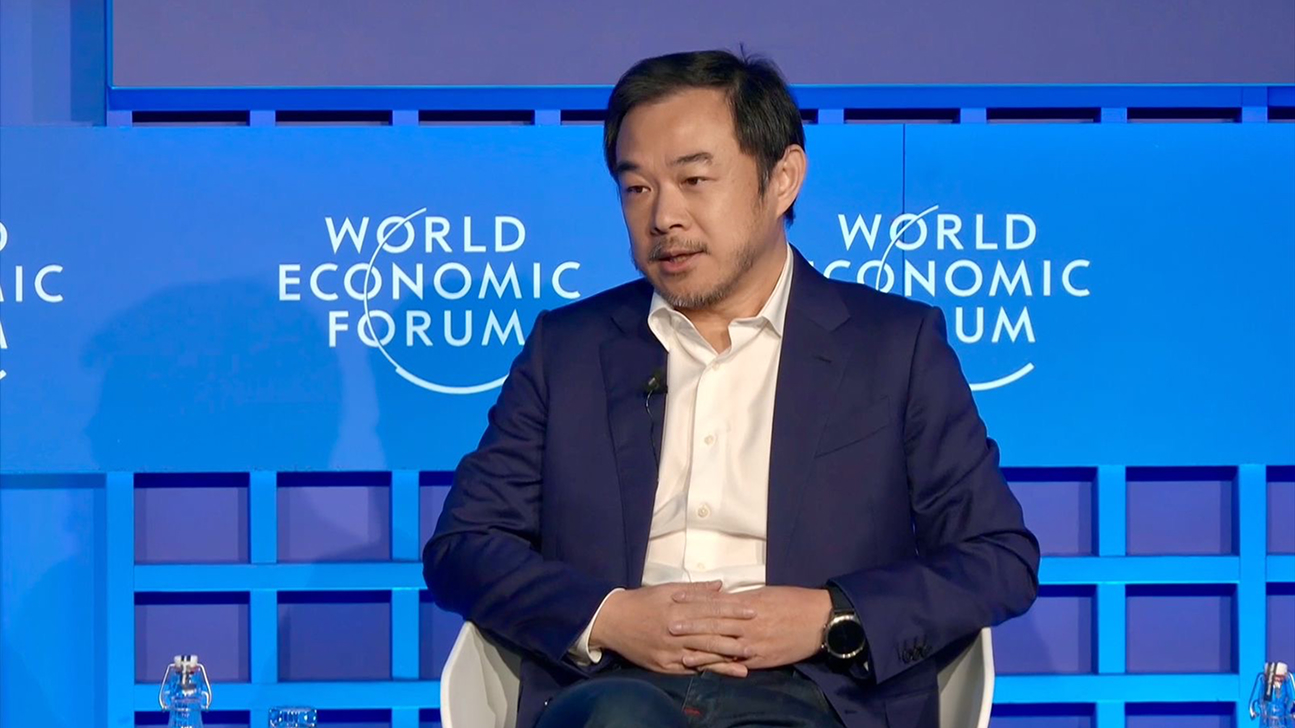

Eric Xing explores the ‘next phase of intelligence’ at Davos

Friday, January 23, 2026

The next phase of artificial intelligence will not come from scaling models ever larger, but from redesigning AI so it can understand the world, plan within it, and contend with real-world uncertainty.

That was the message from Eric Xing, MBZUAI President and University Professor, at a high-profile panel at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where some of the world’s most influential AI researchers, thinkers, and critics gathered to debate what comes next for the technology.

Xing was speaking as part of a session entitled Next Phase of Intelligence, which explored whether progress in AI will continue to be driven primarily by scale, or whether deeper breakthroughs in architecture, learning, and agency are now required.

Moderated by The Atlantic CEO, Nicholas Thompson, the panel also included University of Montreal professor and deep learning pioneer Yoshua Bengio; Stanford professor Yejin Choi, known for her work on continual learning and reasoning; and historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari, whose warnings about AI’s long-term societal impact have resonated beyond academia.

The discussion ranged from technical design choices to existential risk and governance – touching on safety, alignment, and the philosophical implications of increasingly capable systems. And Xing was able to contribute from a unique vantage point.

“We at MBZUAI are among the few – maybe the only university – that is actually building foundation models from scratch,” he said. “From scratch meaning that you gather your own data, implement your own algorithm, build your own machine, train from top to bottom, and then release and serve the whole process.

“It’s important for academics to be players like this so that we can share knowledge to the public, so that people can study many of the nuances in building these models and also understand the safety and risk issues.”

With that experience as a developer, an educator, and a bridge between academia and public understanding, Xing explained that he is skeptical of claims that today’s AI systems are already approaching something like general intelligence. Instead, he argued that they remain far more fragile than many assume.

“AI systems and softwares are actually very vulnerable,” Xing he said. “They are not very robust and not very powerful. If you remove one machine from the cluster, you can crash the whole thing.”

This assertion led him to question what we mean by ‘intelligence’, and urged precision when using the word. “If I tell my engineer to build software that is intelligent, they won’t know what to do,” he explained. “So many people have different opinions on intelligence.

“In my opinion, what LLMs are delivering right now is a limited form of intelligence. I would call it text-based intelligence or visual intelligence, which is actually on a piece of paper in the form of language or maybe video. But this is like book knowledge.”

To further his point, he used a recent personal experience.

“I was hiking in the Austrian Alps a week ago,” he said. “I used GPTs, I used Google, I got all the travel guides and even a Google map in my hand. But when you walk in the mountains, you cannot rely on paper. You have to rely on yourself. You have unexpected situations – the snow is too deep, the weather is no good, and you cannot see the path anymore. So, what do you do? This requires a new type of intelligence that is not available in AI right now, which we call physical intelligence.”

Developing deeper levels of intelligence

Physical intelligence, Xing continued, is where world models come into play. World models are systems designed not just to predict the next word or frame, but also to model how the world works – with the ability to understand an environment, generate plans, execute sequences of actions, and adapt when conditions change.

MBZUAI introduced its own world model, PAN, in November – a new model developed by the University’s Institute of Foundation Models (IFM) that explores how AI systems can understand and simulate the world as it changes over time.

But while PAN marks an important step toward AI that can reason, predict, and plan, Xing was quick to tell the Davos audience that, even here, progress remains nascent.

“World models are still very primitive,” he said. “They are primarily relying on architecture that is a direct offspring of the language model. My work right now is to come up with new architectures that represent the data, do the reasoning, and do the learning using different ideas.”

Staying true to the theme of the conversation, Xing went beyond physical intelligence to look ahead at what might be future phases of intelligence.

“I would call the next level beyond physical intelligence social intelligence,” he said. “Right now, we haven’t seen two LMs collaborating yet. They don’t really understand each other in the form that humans do. There is no definition of self: ‘What is my limitation? What is your limitation? How can we divide a job into two or 100 so that we can break it into parts?’ You can’t ask an LM or a world model to help run a company or run a country because they don’t understand the nuances of interactive behaviors.”

Beyond that, Xing described a further layer he calls ‘philosophical intelligence’. “This is where AI models themselves are curious to discover the world – to look for data and learn things, and then to explain without being asked to explain. This is probably where many people are concerned because that’s where you start to see signs of identity and agency. But we are very far from there.”

Addressing anxieties

The panel’s liveliest moments came when such concerns were raised by the speakers. Harari warned that even relatively simple AI systems have already reshaped society through financial markets and social media – and was alarmed by the lack of attention paid to the potential long-term impacts over decades or even centuries. While Bengio brought up the dangers of misuse, weaponization, and concentration of power.

Xing argued that while these anxieties are important to discuss, a key point must be kept front of mind: AI is software. And for it to cause harm, it must pass through multiple human and institutional checkpoints.

“The idea of a nuclear bomb, for example, is published somewhere,” he said. “But you cannot build it because you need to get the materials. You need to get the labs. There are a lot of checkpoints already. We have learned from generations and centuries of governance and regulation, and human practices have been set in many places already.

“After all, AI is a piece of software. It is software living in the computers. And for it to do physical harm, it needs to go out of the computer, where so many of these checkpoints exist.”

This perspective also informed his defense of open-source AI. For Xing, openness is a natural extension of scientific practice. Closed systems do not prevent misuse, he posited – they merely limit understanding.

“Open source is about sharing knowledge with the general public so that people can use it, study it, understand it, and improve it,” he said . “ I don’t think technology itself is evil – it’s really about the people who use it in the wrong ways. But by close sourcing it, you don’t actually stop that. By opening it, you are promoting more adoption and more understanding.”

For Xing, it is this spirit of openness that will pave the way for new architectures and learning paradigms. These will, in turn, usher in the ‘next phase of intelligence’ – a phase that could take AI beyond today’s narrow, language-based systems toward physical intelligence in the real world, social intelligence in collaborative settings, and towards deeper forms of machine reasoning.

- foundation models ,

- Eric Xing ,

- intelligence ,

- panel ,

- WEF ,

- Davos ,

Related

UAE to deploy 8 exaflop supercomputer in India to strengthen local sovereign AI infrastructure

MBZUAI will partner with G42, Cerebras, and India’s Centre for Development of Advanced Computing to deliver the.....

- partnership ,

- collaboration ,

- summit ,

- sovereign ,

- supercomputer ,

MBZUAI report on AI for the global south launches at India AI Impact Summit

The report identifies 12 critical research questions to guide the next decade of inclusive and equitable AI.....

- Report ,

- social impact ,

- equitable ,

- global south ,

- AI4GS ,

- summit ,

- inclusion ,

MBZUAI marks five years of pioneering AI excellence with anniversary ceremony and weeklong celebrations

The celebrations were held under the theme “Pioneering Tomorrow: AI, Science and Humanity,” and featured events, lectures,.....

- celebration ,

- five year anniversary ,

- ceremony ,

- event ,

- board of trustees ,

- campus ,

- students ,

- faculty ,